- Canada

Americas

Asia & Oceania

Middle East & Africa

Europe

TV SHOWS

VIDEOS

Don't Miss

Most Viewed

Photographer S1

Show: PhotographerLawless Island S7

Show: Lawless IslandWicked Tuna S13 Promo

Show: Wicked TunaPolar Bear Cubs

Show: Wild CanadaShipwreck Treasure

Show: Wicked TunaThe Invaders

Show: Wild Yellowstone: She WolfCritter Fixers: Country Vets S6

Show: Critter Fixers: Country VetsMonkey Hot Tub

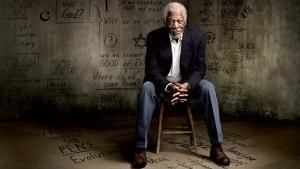

Show: Wild Japan: Snow MonkeysTo See God Inside Your Brain

Show: The Story of God with Morgan Freeman

PHOTOS

Photo of the day

WICKED TUNA

- HOME

- ABOUT

- VIDEOS

- PHOTOS

- LOCATION

- INTERACT

- MORE

- Plight of the Bluefin Tuna

- Still Waters: The Global Fish Crisis

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Bluefin Tuna

- Seafood Crisis: Time for a Sea Change

- Wicked Glossary

- Bluefin Tuna 101

- Gloucester: The Fishing Life

- Captain's Q&A

- Rod and Reel: Bluefin Tuna Fishing by the Numbers

- Overfishing

- 10 Things You Can Do to Save the Ocean

- Seafood Substitutions

- Cook Wise Recipes

- Bluefin Tuna Resources

- Bluefin 360

- LEARN ABOUT BLUEFIN TUNA

BLUEFIN TUNA 101

Biology, Ecology, Economics, and Politics

By Patrick J. Kiger

To understand the bluefin tuna and its precarious ecological predicament—and why its woes are maddeningly complicated to solve—really requires looking at the aquatic giant from multiple angles. Here's a diverse view of Thunnus thynnus, one of the Atlantic Ocean's most remarkable and magnificent creatures.

Biology:

Atlantic bluefin are among the biggest, fastest, and widest-ranging animals on the planet. They can reach lengths of more than 10 feet and weights of up to a ton. Bluefin can swim at speeds over 40 miles per hour when chasing prey or being hunted themselves, and they're also capable of diving to deeper than 3,000 feet. These migratory animals have been known to swim across the Atlantic, covering a distance of nearly 5,000 miles, and somehow manage to return to the same offshore locations again and again over a lifetime that can last four decades.

Marine scientist Molly Lutcavage, who has been studying Atlantic bluefin for the past 17 years, says the bluefin has remarkable physical features that enable it to accomplish such feats. Their streamlined body shape is so optimized for swimming that Pentagon-funded scientists have studied bluefin as a model for Navy torpedoes. Bluefin can tolerate extreme changes in water temperature—from 80°F down to 46°F—that enables them to chase prey in the deep, and they have sophisticated eyes and other sensory systems that also work in the cold darkness. The explanation for their astonishing navigational abilities remains mysterious. It may be that bluefins' acute sense of smell enables them to create a chemical map of the ocean, Lutcavage says. But it's also possible that they may use celestial navigation or rely upon sensing the Earth's magnetic field. (Researchers have found that another species, the yellowfin, has magnetite in its brain, which might facilitate magnetic navigation.)

"Bluefin are a fish without borders," Lutcavage explains. "They can do what they want to do. Only a few big marine animals, such as large sharks, have that much flexibility."

Many fishermen are convinced that bluefin tuna are exceptionally intelligent, and able to figure out fishing tactics and adjust to them. While there isn't research to substantiate that impression, Lutcavage notes that other schooling species have exhibited signs of knowledge transfer, and that bluefins conceivably may have such an ability. "These fish are long-lived, they have incredible sensory systems, and they do have to pay attention to predators such as killer whales," she explains. "They probably do develop evasive tactics as a result."

While it has been long believed that larger, older bluefin are the primary breeders, Lutcavage says that a not-yet-published study will report that smaller, younger individuals are sexually mature as well.

Ecology:

The bluefin is a so-called apex predator, meaning that it resides at or near the top of the oceanic food chain, since its size and physical abilities protect it against most natural enemies. According to a World Wildlife Fund paper, the Atlantic bluefin plays a significant role in the ecosystem by consuming a wide variety of fish—herring, anchovies, sardines, bluefish, mackerel, and others—and keeping their populations in balance. According to the WWF, "ecological extinction of this species would thus have unpredictable cascading effects in the North Atlantic, Mediterranean, and Gulf of Mexico ecosystems and entail serious consequences to many other species in the food chain."

Economics:

Until the mid to late 20th century, bluefin was an abundant but not particularly desirable potential catch for fishermen, since it doesn't taste good when cooked. But changes in the Japanese diet and taste preferences after World War II made bluefin, which is succulent and flavorful when eaten raw, into a profitable staple. Today, bluefin, which once sold for cents on the pound, is so highly prized by sushi devotees that a single 593-pound bluefin caught off the coast of Japan recently sold for $736,000.

Politics:

As overfishing caused the Atlantic bluefin population to decline, the International Commission for Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) introduced a strict management policy for Atlantic bluefin that rapidly developed into what the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution's Oceanus magazine has called "one of the most controversial and politically charged issues in fisheries management." The policy divided the North Atlantic into two distinct populations, one in the Mediterranean and eastern Atlantic and the other in the western Atlantic along the coast of the U.S. and Canada. The western population, which is smaller and has been more severely depleted by past overfishing, has been subject to more stringent quotas.

ADVERTISEMENT

PHOTOS

Bluefin Catch

Join these men and woman in the fishing of one of the smartest fish in the ocean and the hardest...

- All Galleries

VIDEOS

More On Society

![Tim Shaw peels the foam roof off... [Photo of the day - 19 APRIL 2024]](https://assets-natgeotv.fnghub.com/POD/15170.ThumbL.jpg)

![Two crew members film Dr. Pol, Ben... [Photo of the day - 18 APRIL 2024]](https://assets-natgeotv.fnghub.com/POD/15168.ThumbL.jpg)

![The Notre Dame Cathedral. This is... [Photo of the day - 17 APRIL 2024]](https://assets-natgeotv.fnghub.com/POD/15226.ThumbL.jpg)