- Canada

Americas

Asia & Oceania

Middle East & Africa

Europe

TV SHOWS

VIDEOS

Don't Miss

Most Viewed

Photographer S1

Show: PhotographerLawless Island S7

Show: Lawless IslandWicked Tuna S13 Promo

Show: Wicked TunaPolar Bear Cubs

Show: Wild CanadaShipwreck Treasure

Show: Wicked TunaThe Invaders

Show: Wild Yellowstone: She WolfCritter Fixers: Country Vets S6

Show: Critter Fixers: Country VetsMonkey Hot Tub

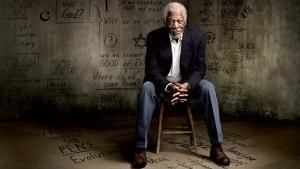

Show: Wild Japan: Snow MonkeysTo See God Inside Your Brain

Show: The Story of God with Morgan Freeman

PHOTOS

Photo of the day

WICKED TUNA

- HOME

- ABOUT

- VIDEOS

- PHOTOS

- LOCATION

- INTERACT

- MORE

- Plight of the Bluefin Tuna

- Still Waters: The Global Fish Crisis

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Bluefin Tuna

- Seafood Crisis: Time for a Sea Change

- Wicked Glossary

- Bluefin Tuna 101

- Gloucester: The Fishing Life

- Captain's Q&A

- Rod and Reel: Bluefin Tuna Fishing by the Numbers

- Overfishing

- 10 Things You Can Do to Save the Ocean

- Seafood Substitutions

- Cook Wise Recipes

- Bluefin Tuna Resources

- Bluefin 360

- LEARN ABOUT BLUEFIN TUNA

GLOUCESTER: THE FISHING LIFE

By Patrick J. Kiger

About 25 years ago, a Brooklyn-born fisherman named Ralph Wilkins read a magazine article about fishermen in Gloucester, Massachusetts, and their pursuit of Atlantic bluefin tuna, the massive migratory predators that can grow to more than ten feet and weigh up to half a ton. Without much ado, Wilkins loaded his fishing boat on a trailer and drove 250 miles up the coast to Gloucester. "I'm into extreme everything, and I wanted to go up against the best," he explains.

Wilkins isn't the first to make the pilgrimage to America's oldest commercial fishing seaport, one that has become a center for bluefin fishing in recent years. If you want to gamble with the high rollers, you go to Vegas. If you think you're the next Johnny Cash or Loretta Lynn, you head to Nashville. If you want to catch the Atlantic bluefin tuna, the biggest, baddest, and most profitable prize in professional fishing, you go to Gloucester. The city of just under 29,000 is a place where men fish to live, and live to fish. And sometimes, as the Gloucester waterfront's statue of the seafarer caught in a storm is a constant reminder, it's where some die doing what they love.

It understates the matter to say that, historically, fishing is Gloucester's signature industry. Rather, say that were it not for fishing, there might not be a Gloucester at all. Gloucester was founded back in the early 1600s, when the English discovered that there were abundant supplies of Atlantic cod offshore. The Pilgrims showed up and began building racks to dry the fish. In the 1800s, Gloucester's fishermen prospered by salting their catch and then peddling it to the Dutch colony of Surinam, where it was used to feed African slaves, in trade for molasses that was used to make rum. Over the next several centuries, they were joined by waves of immigrants from Italy and Portugal, all eager to find a place to make their living off the sea. As recently as the mid-1990s, Italian was the only language spoken on about a tenth of vessels in the local fishing fleet.

Today, their descendants still ply the waters of the Georges Bank, the shallow, sediment-covered undersea plateau that long has served as a smorgasbord for bottom-feeding groundfish such as cod, haddock, redfish, and flounder. During the course of the 20th century, extreme overfishing—including trawlers that pulled nets across the bottom, basically scooping up all the fish—badly depleted the supply of those fish, before government regulators stepped in. Since the late 1990s, the groundfish industry has been relatively stable, with catches ranging roughly from 20 to 30 million pounds annually.

Over the last quarter century or so, the most ambitious and skilled fishermen increasingly have focused upon catching bluefin, the giant predators that roam the Atlantic to feed and reproduce.

Gloucester residents often start fishing as children, and it's assumed that when they come of age, they'll join the family trade. "I grew up doing this," local fisherman Paul Hebert explains. "My father was a fisherman, and my five brothers do it. My mother does it. It's all I know. It's like growing up on a farm, and knowing about cows." They're joined by fishermen, such as Wilkins, who are drawn by the allure of bluefin and the prospect of making thousands of dollars from catching a single giant. The promise of such hefty jackpots obscures the fact that fishing is a hard and not especially profitable way to make a living. The median household income in Gloucester is $60,506, slightly below the median Massachusetts income of $64,509. On the other hand, just 7.8 percent of residents live below the poverty line, fewer than the statewide average of 10.5 percent and significantly below the U.S. figure of 15.1 percent. In part, that's because Gloucester fishermen tend to be jacks of all trades, who fix cars or do electrical work to augment their income from the sea.

Today, the fishing industry is worth about $200 million to Gloucester, including the ripple effect of businesses that benefit from fishing. Even so, the last 20 years have been tough on the city. Gloucester fishermen brought in 88 million pounds of fish in 2010, the most recent year for which numbers are available. That's only two-thirds of the 1990 catch. The local fleet of 100 boats is about half the size it was in 2000, and there was a 20 percent drop-off between 2003 and 2008 alone. Many of the fresh fish-processing facilities that used to provide jobs have closed. With fewer opportunities to attract young workers, the average fishing permit holder in 2008 was 51 years old, and crew members are often that age or older. Local government economic planners worry that the industry's future may be dicey as a result.

Besides the pressure to make ends meet, Gloucester fishermen, more so than most other professions, also must face continual danger. Over the past several centuries, rough weather and accidents have turned thousands of Gloucester residents into names etched into an array of memorial plaques along the shoreline. "There are houses in Gloucester where grooves have been worn into the floorboards by women pacing past an upstairs window, looking out to sea," journalist Sebastian Junger wrote in The Perfect Storm, the bestselling 1997 account of the life and death of Gloucester fishermen.

Junger's book, which detailed the 1991 loss of the fishing vessel Andrea Gail and its crew during a storm, and the movie based upon the book helped turn Gloucester into a particularly macabre sort of tourist attraction. Today, tourism brings in $100 million annually, and visitors drive up Route 128 to see the harbor from which the ship departed, never to return, and stop for a beer at the nearby Crow's Nest, a bar where the lost ship's crew once drank, and whose walls are now adorned with photographs of the actors who played them and their wives in the movie. Cape Pond Ice, which for generations has helped local fishermen to keep their catches from spoiling, now augments that business with a website that sells T-shirts with its distinctive "the coolest guys around" slogan, worn by an actor in the film.

Oddly, as Cape Pond Ice owner Scott Memhard told Cape Ann magazine, many of the tourists who now flock to Gloucester assume the movie was fiction. "They ask, 'Where's the boat?'" he explained. "We say, 'Well, it's at the bottom of the ocean.'"

ADVERTISEMENT

PHOTOS

Bluefin Catch

Join these men and woman in the fishing of one of the smartest fish in the ocean and the hardest...

- All Galleries

VIDEOS

More On Society

![Two crew members film Dr. Pol, Ben... [Photo of the day - 18 APRIL 2024]](https://assets-natgeotv.fnghub.com/POD/15168.ThumbL.jpg)

![The Notre Dame Cathedral. This is... [Photo of the day - 17 APRIL 2024]](https://assets-natgeotv.fnghub.com/POD/15226.ThumbL.jpg)

![Dorado Octopus arms reaching out.... [Photo of the day - 16 APRIL 2024]](https://assets-natgeotv.fnghub.com/POD/15166.ThumbL.jpg)